The Connection Between Blue Light, Operation Paperclip, and Behavior Control

The relationship between blue light technology, neuroscience, and historical government programs like Operation Paperclip offers a provocative glimpse into the ways technology may have evolved from secret experiments to everyday use. While some may dismiss these connections as conspiracy theories, there is evidence to suggest that early neurological research—often tied to government initiatives—laid the groundwork for more advanced and subtle forms of behavioral influence through technology. The introduction of blue light in screens, commonly used in modern electronics, may have its origins in these research programs, designed with far-reaching implications for human behavior and control.

The Evolution of Neuroscience Experiments: From Wires to Wireless

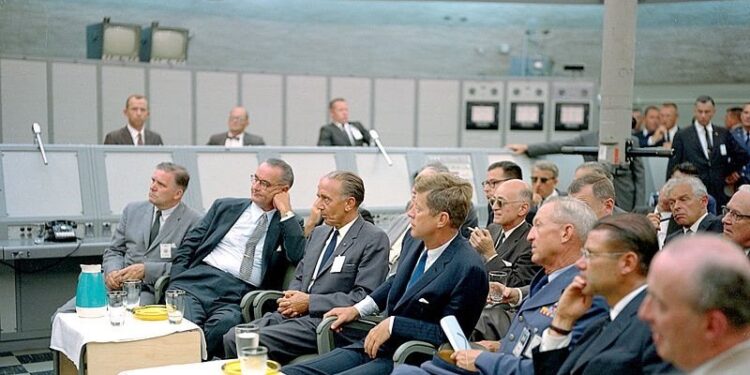

In the mid-20th century, under programs like Operation Paperclip, scientists who had been involved in controversial experiments during World War II were brought to the United States to work on classified projects. Their expertise, particularly in fields such as neurology and psychological manipulation, was put to use in a variety of ways, including exploring how to control animal and human behavior through electrical stimulation.

One of the central figures in this movement was Dr. José Delgado, a neuroscientist whose experiments focused on implanting electrodes into the brains of animals, particularly in regions like the thalamus, to control their actions. Delgado famously demonstrated this control with a bull, using a remote device to alter the bull’s behavior wirelessly. These experiments showcased how electromagnetic signals could influence brain activity and, by extension, behavior—laying the foundation for further exploration into wireless, non-invasive methods of control.

This progression from wired devices to wireless control opened new possibilities for influencing behavior without direct physical intervention. The next step was exploring whether such control could be extended through more pervasive forms of technology—such as light or screens, which could affect large populations in subtle ways.

The Role of Blue Light: A Tool for Influence?

Blue light, the specific wavelength of light most commonly emitted by electronic screens (computers, smartphones, TVs), is known to have a powerful impact on the human brain and body. Research has shown that blue light affects the body’s circadian rhythms, the internal clock that regulates sleep-wake cycles. Exposure to blue light, especially at night, can disrupt melatonin production, leading to sleep disturbances, increased stress, and potential long-term health issues such as fatigue, cognitive decline, and even mood disorders.

Given its physiological effects, it’s not hard to see how blue light could be viewed as a tool for influencing human behavior. Screens emitting blue light can, in theory, alter the emotional and cognitive states of users by affecting their circadian biology. This opens the door to speculation about whether the widespread adoption of blue-light-emitting technology was more than a design choice, but rather a strategic move rooted in early neuroscience research, such as the kind carried out under Operation Paperclip.

Operation Paperclip, CIA Experiments, and the Shift to Electromagnetic Influence

The narrative of blue light as a form of behavioral control connects directly to the neuroscience experiments conducted in the 50s and 60s, particularly at institutions like Tulane University, where brain implants were used to control animals through electrical stimulation. As mentioned, Professor José Delgado and his colleagues pushed this research into wireless territory, moving from direct implants to remote control via electromagnetic fields. This shift suggested that behavior could be influenced not just through invasive methods but through electromagnetic radiation—a category that includes both wireless signals and, critically, light.

The jump from implant-based control to influencing behavior through light and screens could be seen as a natural extension of these early studies. The CIA, heavily involved in psychological and neurological research during the Cold War, was known for its interest in mind control techniques under projects like MKUltra. These projects explored a variety of methods to manipulate human behavior, from psychoactive drugs to electromagnetic radiation.

The introduction of blue light into everyday screens, under this theory, was no accident. If electromagnetic radiation could influence behavior wirelessly, then the consistent exposure to blue light via digital screens could subtly shape human cognition, sleep patterns, and emotional states. While this idea borders on conspiracy, the physiological effects of blue light are well-documented and suggest a deeper potential for influence than we might commonly acknowledge.

The Unseen Consequences: Technology as a Tool for Control

The widespread use of blue light in screens today—present in every smartphone, computer, and television—raises questions about the long-term impact of constant exposure. While the immediate concern is often about sleep disruption, there’s a broader implication about how these devices, and the light they emit, influence our emotional and psychological well-being on a mass scale.

Could this widespread exposure to blue light be a legacy of those early neuroscience experiments designed to control behavior? Perhaps more concerning, could the invisible forces of electromagnetic radiation, embedded in the technology we use every day, be subtly shaping human behavior in ways we don’t fully understand?

Conclusion: A Legacy of Behavioral Influence?

While the connection between blue light and Operation Paperclip is speculative, it opens up a dialogue about how technology influences us in unseen ways. The physiological effects of blue light are well-known, and its ability to disrupt circadian rhythms is a form of indirect behavior modification. When we trace this back to early neuroscience experiments involving electrical and electromagnetic manipulation, it becomes plausible that the technologies we now take for granted may have deeper roots in government programs aimed at behavioral control.

The question we are left with is this: How much of our interaction with technology, especially through screens, is shaping us in ways beyond our immediate awareness? And how much of this influence is intentional, a continuation of research that began in secretive government laboratories decades ago?